The Wonder Report: September 3, 2021

The Weight of Memory

I’m so glad to be back after a brief hiatus. Thank you for waiting patiently while I spent time with family, continued to grieve for my mom, and envisioned what life might look like going forward now that “caregiver” is no longer in my job description.

One thing that will look a little different going forward is the shape of The Wonder Report. It will still come to you weekly with an opening essay, revolve around a monthly theme, and contain all the various features you have come to expect: art, nature, faith, science, books, and more. However, all the features may not be part of every issue. My goal is to make The Wonder Report both more condensed and more engaging.

For instance, rather than sharing a list of links each week, I might share only one essay, with more commentary and some questions to consider. Rather than share an artist’s work for four weeks in a row, I might invite you to consider one piece more intently. And while I will still offer occasional advice for writers, you might find journaling and writing prompts throughout The Wonder Report rather than just in one section.

I’m also planning some supplemental content each month just for paying subscribers … a feature I’ve been hoping to add for a while now.

So grab a cup of tea or glass of lemonade, get comfortable in your favorite chair or hammock, and join me once again for the Wonder Report.

This month, we’re talking about memory.

1. Memory’s Map: You Are Here

Mom had been gone only a couple of days, and we were already going through her things. Had to, really, because her facility offered us no extra time to put the task off, no grace period to catch our breath before emptying her room and storage locker. My brother was here from out of town, too; he’d made it here in time—just in time, really—to say goodbye to Mom. And he wanted to help with the difficult task.

The storage locker would be easy to clear out. Everything was already packed in boxes and plastic totes. So the guys started there. I took duffel bags and boxes to Mom’s room. By the time the storage unit was empty, I could have things packed and ready to load, I told them.

"Are you sure you want to do it by yourself?” my brother asked. The last time we were in the room, Mom was still there.

“It’ll be hard, but I’ll be fine,” I said. Now that she was gone, I thought it would be easier.

But the minute I walked in, the tears started. Her special air mattress and oxygen unit had already been removed by the medical supplier. The carpet was stained and dirty. Had it been like that as we all huddled around Mom’s bed yesterday? Is that actually why it looked like that today?

As I opened her dresser and began filling the duffle bag with pajamas, I remembered Mom’s long obsession with all things fleece and seersucker. For my whole life, Mom had worn a different set of pajamas every night, repeating them only after several days. She had warm fuzzy pajamas for the winter; short, light-weight pajamas for summer. If anyone asked for gift ideas for mom, I always said pajamas. Months earlier, when the nursing home staff had asked if Mom wouldn’t be more comfortable in gowns now, I knew the answer without even asking her, though I did. No, she preferred pajamas. The end.

I moved to the wardrobe and began packing shirts, long sleeves, short sleeves, 3/4 sleeves. I remembered the ones I’d gotten for Mom just last Christmas and others that she and I had alike. We always laughed when I walked into her room wearing the same shirt she had on. Often, we’d snap a photo to commemorate the happy accident. On the table beside her recliner, I grabbed stacks of letters from my Aunt Pat who had written every week since COVID started, maybe even before. I remembered sitting in a metal folding chair next to Mom’s recliner reading those letters to her, sometimes in full PPE.

As the totes and boxes got fuller and fuller, so did my heart with all the memories of the past few years. The good memories of pizza parties and puzzles and walks in the garden and BINGO. But also the hard memories of physical decline and difficulty communicating and the slow but steady loss of freedom that came for years following Mom’s stroke.

When I was still sobbing after 20 minutes of packing, I texted my husband: “I can’t do it by myself.”

But down in the basement in the middle of the storage room, the text never came.

So through tears and memories, I continued to pack. But I wasn’t really alone.

::

A couple of days later, with a mound of mom’s possessions filling half the garage, we began a more intentioned pass through the little Mom had left. Over the past eight years, Mom had moved from a farmhouse, where she and my stepdad had lived for almost 25 years, to a three bedroom house in town, to a two-bedroom apartment near me, to a one-room apartment at her retirement center, to one room—her final room—in the skilled nursing unit. She did the first round of down-sizing herself, but from there, the task had fallen to me. By the time my brother, my husband, and I were making our final pass through just three days after she died, I’d personally sorted, packed, and moved every one of her possessions at least three times.

We made piles to donate and discard, smaller piles to keep. We selected a few things for ourselves and family members that we thought would be special. All the photo albums and pictures were set aside to take to Mom’s celebration of life service. And then there were the totes filled with old cards and letters. I have my own such boxes in the basement, correspondence that’s sacred because it exists not because of what it says, documented evidence that I was thought of and cared for by others. I knew these letters were what other people had written to Mom, not Mom’s own thoughts and reflections. Still, I couldn’t just toss them.

“Save those,” I said. “I’ll go through them later.”

Days went by. The celebration of life happened. My brother left. We made an attempt to get back to work and school and life. And one evening, I pulled out one box of the letters. Many of them were birthday and Christmas cards, with little more than a signature. Some were sympathy cards Mom received when she lost her own mom and husband years earlier. Then there were the letters in my own loopy handwriting, dozens of them from the years 1989 to the early 2000s.

I opened one from my first semester of college and was surprised by how homesick I had been. I opened another and another, reading about the pain of transition into adulthood. I found another stack from the summer after my junior year when I worked on the southern coast of Maine. I was so homesick that summer Mom had to fly out for a week to keep me from driving my little red Chevette back to Indiana. I read letters from my days living in Atlanta, Georgia, Northwest Indiana, and Chicago. And though the letters were about me and my life, because they were written to Mom, suddenly I remembered what she was like then, too. And mostly I remembered who we had been together, mother and daughter.

From the perspective of my younger self, I remembered how Mom had created a safe and nurturing place for me to grow up, I remembered how she had trained me and modeled for me what it was like to do hard things, I remembered how much she struggled to let me go when it was time, and I remembered who I was then and still am now because of Mom.

For the past several years, I haven’t spent a lot of time remembering what life used to be like before Mom’s stroke. I didn’t linger over memories of Mom pouring herself into our lives, always busy and active, because it made it harder to accept life as it had become for her: small, limited, isolated. I told myself that when she was gone, I could remember all the good times. But I had stopped remembering so long I was afraid I had forgotten. Those letters were the key that brought it all back.

::

I’ve been sitting with a lot of memories over the past few weeks, letting them wash over me whenever they come. But the problem with memory is that it’s slippery, like a bar of soap. The harder we try to hold onto it, the more likely it is to slip out of our hands. Sometimes I jot down a few notes, hoping the memory will last a little longer. (That’s the writer in me.) But just as often, I let them go as quickly as they came. They’ll come again when I need them.

Because so many things make sense only when they’re remembered. It’s what happened with the disciples of Jesus. Though Jesus taught them a lot while he walked the earth, and though the disciples grew in their faith through each miracle he did and parable he told, they never really understood the purpose of his kingdom until after his resurrection, when “they remembered his words” (Luke 24:8).

That’s why I wanted to take some time throughout September to talk about memory: what it is, what it isn’t, what it can and cannot do for us. I resisted remembering for all those years because I thought it would be too painful, and maybe that was true. Remembering can seem like taunting when all that was good and beautiful is taken away. But it can also be a map, a sign along the way, a landscape marked with the genus and species of everything that’s growing around us, showing us that what is now, what is here, what is inside us didn’t come from nowhere. We are from somewhere, we are from someone, and our memories tell us from where and from whom.

I wonder … are there periods in your life that you choose not to remember? Why? What do you think you can learn by revisiting those memories? Do you think it would be helpful to talk with someone else about the memories?

2. Photographic Memory? Taking Photos Helps You Remember Some Things

As I looked back on photos of Mom in preparation for her celebration of life, memories of her younger years came flooding back. Some of the memories included me; others were stories she’d told, represented by the photographs. It made me wonder: are the memories real, or had the photographs become an external storage drive, of sorts, and looking at them like reloading information I had long forgotten?

According to a 2017 study published in the journal Psychological Studies, taking photos of people and events does help you remember them later … and not just by reviewing the photos.

“Taking pictures boosted all visual memories, not only the specific items that were photographed,” writes Mike Battista, a staff scientist at Cambridge Brain Sciences. “Rather than being a distraction or a crutch, cameras appear to have provided an overall boost to visual memories.”

But the deeper memories tended to be visual only. Researchers found that those who spent time taking photos also had weaker auditory memories.

Interestingly, the visual memories improved even for those who took at “‘mental photo’—that is, just pretending to have a camera,” but that practice had the same negative effect on reducing auditory memories.

Here’s the bottom line, writes Battista: “Memory is closely related to attention. You remember what you pay attention to, and if you have a camera that you plan to use, you’re paying attention to what everything looks like.”

I wonder … do you like to take photos? What tends to be the object of most of your photos? What’s been your experience with remembering what you snap? How do your other senses—auditory, olfactory, somatosensory—play a role in your memories?

3. We Weren’t Happy Before the Pandemic, Either

In a beautiful essay for The New York Times, Dr. Esau McCaulley, professor at Wheaton College, writes about the wonder of memory … how sometimes new circumstances trick us into seeing the past differently than we originally experienced it. For instance, Dr. McCaulley suggests that the pandemic has tempted us to see pre-COVID times as “normal,” longing nostalgically for a return to all that was right and good in the world. When in fact, these past couple of years living with COVID have shown us that our “normal” life was neither how we remember it or all it was cracked up to be. Dr. McCaulley suggests that now, after a year of collective trauma, we’re better able to see things as they really are … and do something about it.

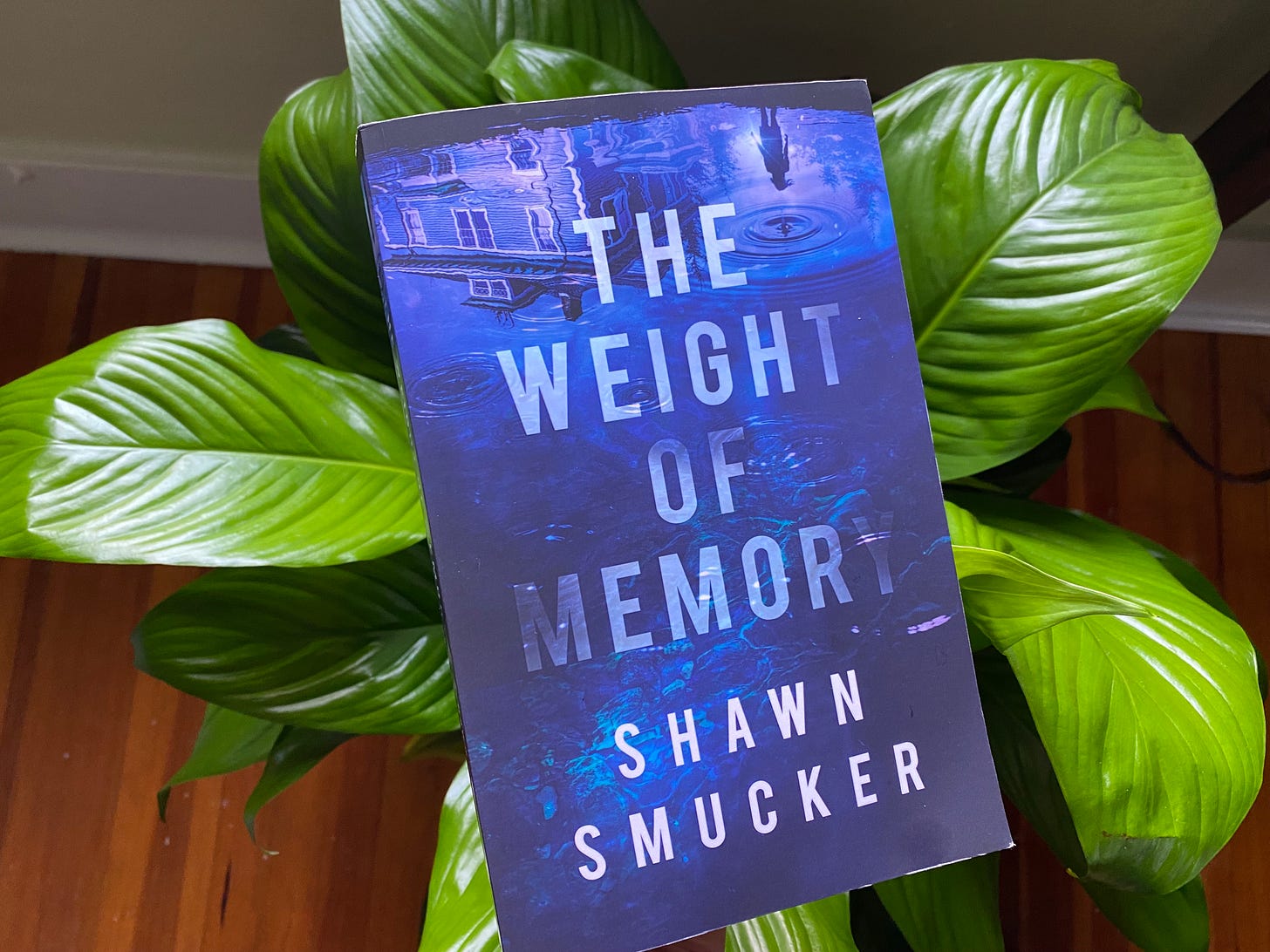

4. The Weight of Memory by Shawn Smucker

“How is it that a mind can contain so many memories? Where does it all fit? Into what nooks and crannies do we place these recollections of love and sadness, horror and joy? Into what tiny space of our minds do we put a person we met long ago, or a disappointment, or a lie? And where do memories go when we forget, and how is it that they can come rushing back, unbidden?”

This book of magical realism is filled with questions about memory: Who are we when we don’t remember the past? Whose memories should we believe? And what responsibility do we have to share our memories with future generations? Methodical, lyrical, relatable—this novel made me want to reexamine my own life and relationships to be sure my own memories are real.

5. SUMMER WRITING SERIES: When I Write … with Sarah Guererro

When I write, I want to quit. Sometimes I do. Sometimes I swear off for the day and sometimes I swear off writing forever.

But! Eventually! I remember who I write for, and I drag my battered ego and every one of my fears and all of the negative voices in my head back to my computer and we all sit down and I write.

I know how courage and honesty works. If you can do it, I can do it. If I can do it, you can do it. If my only spiritual gift is going first, so be it. I will go first. I will write for the women who were brave enough to go before me, and I will write for the women who will be brave enough to come after me, and Holy Spirit-willing my words will be one more drop of creative water in this mighty river.

Try it yourself. Think about your ancestors, women whose stories weren't or couldn't be told, and think about the women you know whose stories need to be told, and maybe imagine some women coming after you. Write with and for and through them and marvel at your place of belovedness in this great cloud of witnesses.

Sarah is the author of Break Through: Disarmingly Joyful Ideas About Fear, Guilt, & Shame in Motherhood. As a woman of mixed ethnicity, she’s learned to feast on Jesus’ goodness in the in-between places. She lives with her husband and four children in Austin, Texas. You can learn more about Honesty is My Gift, Sarah's monthly newsletter/essay, here.

Thanks again for sharing this time with me. If you’d like to send me a note or ask a question, you can hit reply and end up in my inbox. Or you can also leave a comment on this newsletter, which will live in the archive over on Substack. It’s one of my favorite features of this platform.

Thanks again for being a subscriber. One of the reasons I write is because of readers like you!

Until next time,

Charity

I think of memory as a sacred act. Thanks for these reflections.

Oh Charity, this is absolutely beautiful. What a gift to read your words, and in them such encouragement, companionship through your sharing and so much food for thought. Your reflection on memory as a map is extraordinary, powerful and deeply moving (and helpful. I want to return to your words again and again). Welcome back - I loved every bit of this WR and your plans for how it’s evolving.