The Wonder Report: November 12, 2021

A Sense of Place

Happy Friday! The sun shines brightly here in Central Indiana, and the breeze blows briskly, stirring the sugar maple leaves on their branches just outside my window. I can’t wait to get outside for a walk with my husband and our two dogs at lunch time.

We’re continuing our theme of the senses this week, and I can’t help but think that November is the perfect month for this conversation. It’s a time of transition, a prelude to a busy holiday season, and the opportunity to feast before the things get too busy. I can hear November in the rustle of leaves. I smell November in the dampness and smoke. The tastes of November are comforting and familiar: sage and butter and pumpkin spice. I see November in its flurry of change, from bright and colorful to dull grays and browns. And the feel of November runs the gamut from a light sweat while raking to cozy and warm next to the fireplace.

Of course that’s how I sense it here in the US Midwest. It might come to you differently where you are, which is exactly what we’re going to talk about this week: how our senses help us know where we are.

Let’s jump in.

1. The Nose Knows (and the Eyes, Ears, Tongue, and Fingers, Too)

Whenever the topic of the five senses come up, I often tell people about the smell of my Aunt Sue’s house. I’m not sure I can describe it: part cigarette smoke, part dog hair, part perfume. Surely the fields that surround her property and the gardens that fill out the landscaping around her house add an earthiness to it. And often, there’s a hint of whatever she and my Uncle Jim had for lunch. But if you blindfolded me, flew me around the world, dropped me off at her house without telling me, and then asked me where I was, I’d take one sniff and tell you: Aunt Sue’s.

Of course it’s not just the smells that tell us where we are. There are four maple trees on our street: our sugar maple, plus the one in front of our next door neighbor’s house, and the two red maples in front of the house next to them. I don’t know what it is about these trees, but when I’ve taken pictures of our street during peak leaf season and posted them on social media, people have guessed which street it is without me otherwise identifying it. The sounds of a place also remind us where we are: the train whistle, the rustling of leaves, the bird song and the wind chimes. Sometimes a place just feels a certain way: rugged, frigid, balmy, or flat.

When we visit a place for the first time, our first experiences, maybe even our first memories, come to us from our senses. We take in what’s around us and begin making connections with all the other places we’ve been. Our senses also tell us what’s new and different about the familiar places we return to again and again. Through our senses, we understand we’re here not there. We feel at home or like a stranger. We remember all the places we’ve been before.

::

Writers often are advised to use sensory descriptions when establishing the setting of a story or article. Ann Kroeker has a whole podcast on multisensory writing, and she suggests that writers tap into at least three different senses to “bring your writing to life.”

In great writing, these sensory descriptions do more than just set the scene though. They create places that readers know and remember as if they’d actually been there. I think of the Shire from The Hobbit, Hogwarts from the Harry Potter series, Mitford from Jan Karon’s Father Tim series, Pemberley from Pride and Prejudice, and Port William from Wendell Berry’s fiction. Obviously I’ve never been to any of these places, but I can see them in my imagination, I can smell them and hear them and sometimes even taste them.

Most of these fictional places are likely based on the author’s sensory experiences in real places, even the otherworldly settings like the Shire and Hogwarts. But those sensory experiences aren’t just being translated from the real world into the imaginary. Even if a writer is creating a world different than the one she inhabits, how she experiences the place where she works will necessarily influence her work in one way or another. As Wendell Berry says in “Imagination in Place,*” “The fiction I have written here [on his farm in Kentucky], I suppose, must somehow belong here and must be different from any fiction I might have written in any other place.”

What if that is also true of all the other kinds of work we do?

Some of those connections are obvious: people who work on or with the land (farmers, gardeners, landscapers, ecologists, loggers, excavators, builders) are forced to embrace the gifts and challenges of a place. Their senses are like another tool in their bag to help them make plans, assess needs, and evaluate and solve problems. What they do is so specific to their place that their work would be substantively different if they were to do it in another place.

But what about other kinds of work? How are our housekeeping and parenting, our accounting and shopkeeping, our teaching and lawyering and warehouse working and cooking unique because of the places we live and the experiences we have there with our senses? Or another way to ask it is this: If you moved to another place, how would you live your life and do your work differently? And if the answer is “not at all,” do you think that’s a problem?

::

When writers are advised to use sensory descriptions, there’s another piece that often gets lost: Be specific. Don’t tell us the flowers smelled good: help us smell the lilacs, aromatic and sweet, like honey. Don’t tell us the dessert was delicious. Invite us to taste the chocolate chip cookies, crisp on the outside, gooey on the inside, with just the right blend of butter and chocolate and nuts. Don’t tell us the trees turned colors. Show us the flaming reds and oranges of the maples, the shimmering golds and yellows of the oaks and tulip poplars.

Specificity of senses moves us toward a deeper attentiveness: beyond just what to how and where and why. It helps us notice when we’re in Chicago rather than Charleston; Louisville instead of Lewiston; Washington state versus Washington, D.C. It also helps us understand why it matters. Being specific honors and highlights what we have in common—the Gingko Biloba tree, of the fan-shaped leaves that’s native to China, is also growing in my neighbor’s yard—but also we hold differently—not once have I smelled my neighbor cooking stinky tofu, which also is native to China.

But what if I had a neighbor from China? Ahhh, yes.

Not only do our specific places help form our work, as Berry suggested above, they actually form us as people. What we see and hear and smell and taste actually make us who we are; they do part of the work in defining who we are, where we’re from. They influence what we believe, how we communicate, where we’re heading.

That doesn’t mean every person from the same place is the same, but it does mean that every one us would be different if we were from a different place.

I wonder … how would you describe the place you live? Have you lived in other places? How would you describe those? Use your senses and be as specific as possible. How do you think your places have influenced your life and your work? What differences could you imagine in your life if you lived in a different country or even just a different town?

2. The Where I’m From Project

It’s possible you’ve already heard of this poetry project or even tried out the prompt for yourself, but if not, I want to point you to the Where I’m From Project, created by George Ella Lyon.

Lyon’s poem “Where I’m From” grew out of her response to a poem from Stories I Ain't Told Nobody Yet (Orchard Books, 1989; Theater Communications Group, 1991) by her friend, Tennessee writer Jo Carson. Here’s how Lyon describes the process:

In the summer of 1993, I decided to see what would happen if I made my own where-I'm-from lists, which I did, in a black and white speckled composition book. I edited them into a poem — not my usual way of working — but even when that was done I kept on making the lists.

Lyon’s poem is a beautiful and highly specific list of sensory experiences she had as a child that helped shape who she is now. That poem later became a writing prompt that’s been used at family reunions, in classrooms around the world, in juvenile detention centers and prisons, and even in refugee camps in the Sudan.

You can read Lyon’s poem and more about the project here. After you’ve read it, click on the button below for a template to help you write your own Where I’m From poem. Every time I’ve used it in groups, the results are very moving.

By the way, if you do write a Where I’m From poem, will you share it with me? You can leave it in the comment section or just reply to this email and send it to me directly.

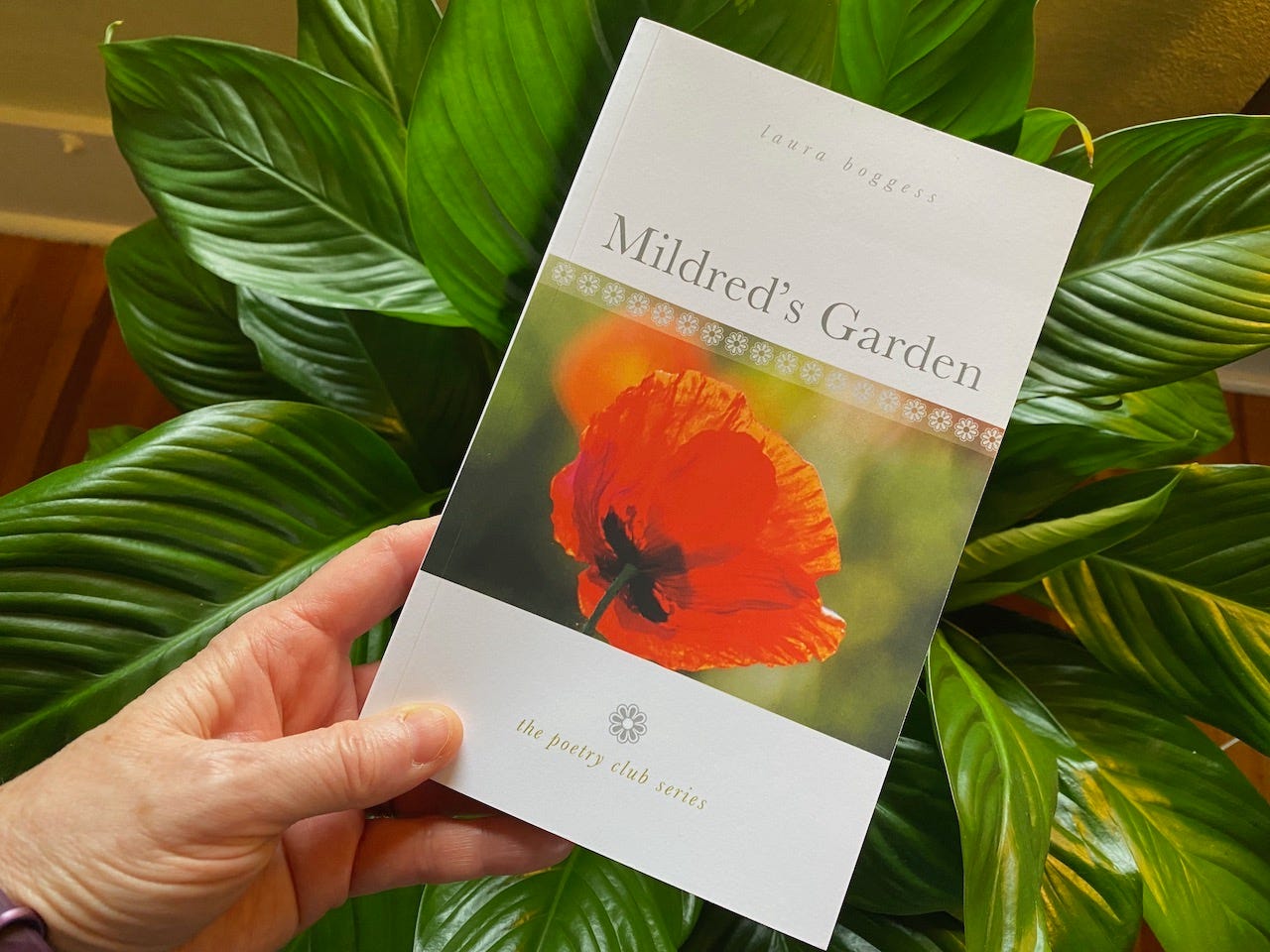

3. Mildred’s Garden by Laura Boggess {BOOK GIVEAWAY}

My friend Laura Boggess recently published a new novel called Mildred’s Garden, which won the West Virginia Writer’s Competition. It’s what Laura calls a “double refugee, Instagram love story.” Here’s how the publisher describes it:“

A gentle musician (Sam) has been noticing a fan's (Mildred's) Instagram and feeling the pull. He's hopelessly attracted when he sees her in a field of poppies or with sunflowers or talking about her new bed and breakfast business in West Virginia. Before he knows it, he's calling her Moonflower and wondering whether she'll let him into her life beyond the screen.

“What he doesn't know, at first, is that they share a part-Vietnamese heritage-and that Mildred is about to take a refugee family into her life. At the same time, his own beginnings as an adopted son are missing important details he didn't think he'd ever care about, until a long lost cousin comes onto the scene. Sam also doesn't know that Mildred's got a secret that's been keeping her from any new relationships for 15 years.

“In a whirlwind get-to-know-you-with stops and starts, plus poetry and a few surprises-the alluring promise of beginning again arises for Sam, Mildred, and others who end up in their orbit.”

I recently interviewed Laura about the book’s connection with our theme of senses and specifically to their connection with place. Here’s a little bit of what she shared:

CHARITY’S QUESTION: What role do you think senses play in Mildred’s Garden?

LAURA’S ANSWER: I think I deliberately write in a way to engage the senses in all my writing. When I blogged short essay-type writing, it was largely sensory based. My poetry is too. I think it’s just a way of drawing the reader into the world of the story. It’s definitely plays a big role in my writing.

CHARITY’S QUESTION: The characters in this book also seemed to be particularly attuned to their sensory experiences. Do you think people in real life generally are as attuned in this way?

LAURA’S ANSWER: I do think some people are wired more that way. And as artists or writers, you can certainly hone that awareness. Your training will make it more fluent and heighten your awareness.

But I think that every day life creates this taking for granted of those small noticings. Part of what artists do is create a space for those people who aren’t as inclined to notice sensory experiences, to give them the space to slow down and reflect on their own senses and what they’re seeing and feeling. Just giving them that opportunity.

I notice even in myself—and I’m kind of wired to notice senses more—that I can get caught up in the schedule and the work I have and my to-do list. But if I’m on vacation or if I’m on retreat and I create a special experience designed for slowing down, then I’m much more in tune to what I see and touch and feel. So I think part of what I try to do as a writer, is to create space for other people to feel that.

(By the way, paying subscribers will receive an email later this weekend with a link to the video of the whole interview! It’s only 22 minutes long and filled with wisdom about senses, place, and writing.)

Now, for the best news!

I purchased two extra copies of Mildred’s Garden to give to two lucky readers! Just leave a comment below (or reply to this email) with a story about a specific sensory memory you have of a favorite place. I’ll draw a winner next Thursday, November 18, in time to announce in Friday’s Wonder Report.

4. 風物詩 (ふうぶつし) — “Fuubutsushi”

In my reading this week, I came across this beautiful Japanese word, Fuubutsushi. It essentially means “nostalgia,” but according to Japanese language and blog, FluentU, it particularly means “nostalgia that occurs when something triggers memories from a specific season.”

“The term roughly translates to ‘seasonal tradition.’ If the smell or sight of something reminds you of a particular season, it’s a 風物詩 moment.”

5. The God of the Garden by Andrew Peterson

Andrew Peterson’s new book, The God of the Garden, was published by B&H a few weeks ago. While I haven’t read it (my copy is being shipped as we speak), I found this clip of him reading a chapter called “Places and No Places,” and it fit so perfectly with our theme this week, I just couldn’t resist linking here.

Here’s how he describes what this chapter is about:

“I’ve been passionate for a while about place, and the way we use places, the way we shape the places around us, what its says theologically and anthropologically, about what we think about God and what humans are for and what the earth is for. I think a lot of the way we build things—infrastructure and homes—is kind of a reflection of what we think is most important.”

You can find the chapter reading at about 2:36 in the video below.

Thanks again for sharing this time with me. As always, if you’d like to send me a note or ask a question, you can hit reply and end up in my inbox. Or you can also leave a comment on this newsletter, which will live in the archive over on Substack. It’s one of my favorite features of this platform.

Thanks again for being a subscriber. One of the reasons I write is because of readers like you!

Until next time,

Charity

I love this idea of writing a "Where I'm from" poem. I will give it a try and may or may not share!

I, as Sue commented, also want to try the template - it’s already got me thinking! So good. And I love the Japanese link with seasonal sensory memories. I could talk to you for hours about that! Wonderful.