The Wonder Report: February 19, 2021

A Livelier Sense of Need and Suffering

Happy Friday, friend!

Earlier this week, our area of central Indiana received a thick covering of snow. The official measurement was somewhere around 10 inches, though with the four or five inches already on the ground, and the three more inches we got later in the week, it feels more like two feet. And maybe even more so because we’ve waded through it in our boots, plowed through it in our all-wheel drive SUV, and lifted, carried, and dumped a fair amount of it with our shovels. However you measure it, there’s a lot of snow out there.

At some point early in the day on Monday, when the snow was still coming down pretty hard, I heard scraping in front of the house. I peeked out the window to find our neighbor Nate shoveling our sidewalk. Last week after another snow, Steve had shoveled theirs. Later in the day, I heard tires spinning. When I peeked outside again, a different neighbor’s car was stuck. Steve and I donned our boots and coats and headed to her driveway to help dig (and push) her out. There’s nothing like a good weather event to remind us how weak and needy we all are in the face of nature.

I was thinking of the way we depend on and share with our neighbors when I read Scott Russell Sanders’ essay called “Neighbors” from The Way of Imagination. He writes about the area of rural Ohio where he grew up, how neighbors were always helping each other out.

“Neighbors would loan tools, offer rides to town, share garden bounty, listen to happy news or sorrows, visit shut-ins, and swap work,” he writes. But he also sidesteps any romantic notions of neighborliness, recalling that “there were grumps and gossips among us, but no saints.” In fact, he said the reason his neighborhood functioned so well as a safety net for all who lived there was not because some were more equipped to do the helping than others, but that “people knew that sooner or later they would need a hand or a hug, a recipe or advice.”

“Knowing their own vulnerability, they had a livelier sense of what others needed or suffered.”

I love the words “livelier sense” here. They evoke the way of imagination that runs throughout Sanders’ book. How many times have we come to the side of a suffering friend or neighbor and said, “I can’t even imagine what you’re going through”? Of course that’s almost always better than telling someone, “I know exactly what you’re going through.” Those words often strip away the comfort we might otherwise have offered by making our friend’s suffering more about us. But what if instead of “I can’t imagine” or “I know exactly,” what if “knowing our own vulnerability” brought us into the quiet posture of “I can try to imagine,” that’s followed with empathy?

That’s how it went on Tuesday as we were shoveling the snow from our neighbor’s driveway. We could try to imagine what it would be like to be snowed in as a single mom with three kids. That’s why we went and helped. And then, as we were pushing her SUV out of the icy ruts and she told us that her dad had died recently, unexpectedly, we could try to imagine how helpless and lonely she felt.

“We were really close,” she said.

::

At midweek, with the ground still buried in snow, Steve and I marked each other’s foreheads with ashes, remembering once again that “we are but dust, and to dust we will return.” We’d gotten the zip-locked baggy of ashes mixed with frankincense during our in-person worship service on Sunday; our tiny church plant of around 20 meets masked and distanced in the borrowed youth room of another church’s building.

During our Ash Wednesday Zoom service, the priest reminded us that Lent shines a light on “the need which all Christians continually have to renew their repentance and faith.” And he invited us to spend the next few weeks in self-examination and repentance; prayer, fasting, and self-denial; and reading and meditating on God's holy Word.

As part of the liturgy, I read from Isaiah 58, a passage where God also invites his people into a season of fasting, but not in the usual ways, not as “a day to show off humility, to put on a pious long face and parade around solemnly in black” (Isa. 58:5, The Message). Rather, “This is the kind of fast day I’m after,” God says, “to break the chains of injustice, get rid of exploitation in the workplace, free the oppressed, cancel debts. What I’m interested in seeing you do is: sharing your food with the hungry, inviting the homeless poor into your homes, putting clothes on the shivering ill-clad, being available to your own families” (Isa. 58:6-7, The Message).

Later, when I wiped the gray crust from my forehead before bed, I thought about how this season of repentance sounds quite a lot like Sanders’ description of being a neighbor above. When we rightly assess ourselves through self-examination and repentance, we can humbly serve others through fasting and self-denial. And it doesn’t take too much imagination to see that Sanders’ statement about knowing our vulnerabilities and having a livelier sense of others’ needs is really just a fancy version of Jesus’ command to love our neighbors as ourselves.

Wonder Challenge

How are you observing Lent this year?

Sometimes, I seem to complicate Lent, with elaborate readings and complicated fasts. And I’ve nearly done that again this year, with lots of rules about when and where I can do this and that. But for all the ways I overthink Lent, I’m also hoping that I can observe this season by making more space to hear from God: to pay attention when His words stand out to me, to believe Him when he points out a sin I need to deal with, and to obey him when he brings to mind a person who needs loving on. What about you?

Here’s the challenge: Read Isaiah 58 in a few different translations. (Biblegateway.com is a great tool for that.) Based on your reading, what do you think God might be inviting you to do differently this Lent?

This and That

Here are a few articles, essays, and more to give you hope, to make you think, to grow your faith, and as always, to help root you in love.

Considering the Trees on Ash Wednesday by Isaac S. Villegas for The Christian Century. I love the spiritual imagination of this post that uses the ashes of Lent’s beginning to remind us “that the material of our bodies is in solidarity with the rest of creation” and particularly the ways that “the palm ashes of the ritual affix us to cremated trees, our skin welcoming their remains into our bodies.” It reminds me of Paul’s teaching in Romans 8 that humans aren’t the only ones longing for redemption, that all of creation is groaning to be set free.

From the essay: “For now, during these brief years together with our neighbors in this habitat, we wear ashes on our foreheads once a year as a kind of prayer—to offer ourselves as a walking plea for the redemption of all creation.”

Lent Is a Time to Sing the Blues by Derek Sweatman for Christianity Today. I’d never thought about the ways this “music and sentiment that were born in the fields of American slavery” perfectly captures the pain, self-reflection, and longing of the Lenten season. So many of our worship songs are about hope and joy and resurrection, and come Easter, we’ll sing those with gusto (well, at least in our hearts. We still aren’t publicly singing in our little congregation because of COVID). But during this season, I can’t think of a better way to capture Lenten angst than with the grit and grind of the blues.

From the essay: “Allowing the nature of the blues to have a seat at the table of church life is good for the congregation. Reflective sadness has a place in the life of a congregation. There is ‘a time to mourn,’ said the writer of Ecclesiastes (3:4), and more than any other season, Lent gives the church dedicated space to sorrow together.”

Giving Up the Charade by Charity Singleton Craig for Fathom Magazine. I’m so glad for the timing of the publication of this piece because it fits well within this discussion of imagination, empathy, and love. Basically, it’s a examination of what it means to die to self, which is the high calling of believers as we seek to love others. But is there a way to have a “livelier sense” of our own needs as a way to enter into this vulnerable posture?

From the essay: “Throughout scripture, the call to love and sacrifice for others is never commanded in this language of self-erasure that Hauser employs. We don’t diminish ourselves to exalt others. Rather, as Jesus said, we are called to love our neighbors as we love ourselves.”

More from The Wonder Report

Articles and newsletters you might have missed from The Wonder Report Substack page.

The Wonder Report - February 5, 2021 — The Way of Imagination

The Wonder Report - February 12, 2021 - Useless Beauty and What We Make of It

Visually Speaking

In this section, I'll highlight visual and performing artists and talk about how their work inspires mine. I'd love to hear about artists you love and whose work you admire.

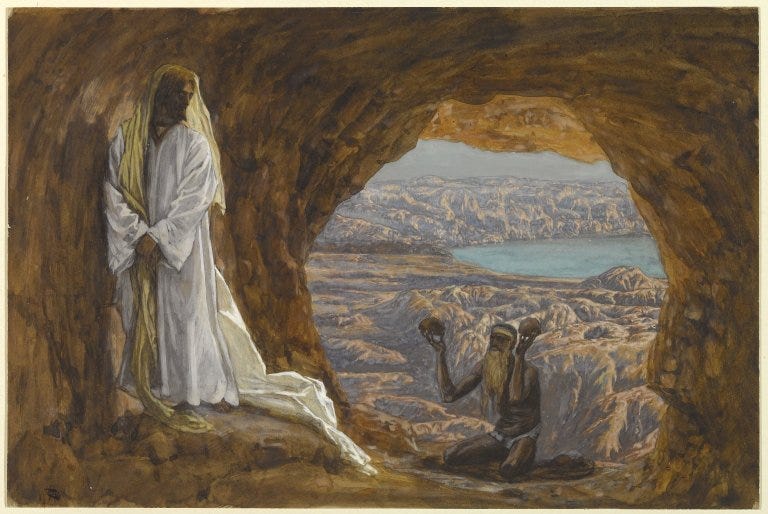

The work of French painter James Tissot always inspires me to think about God’s work in the world and in my life differently. Two years ago, I used several of his paintings in a Lenten series on my blog. Today, I wanted to offer another painting for your reflection as we come again to this season of repentance.

Jesus Tempted in the Wilderness (Jésus tenté dans le désert) by James Tissot - Online Collection of Brooklyn Museum; Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 2006.

In an archived article in America Magazine, editorial director Karen Sue Smith describes Tissot’s work this way: “To believers, Tissot’s images reveal something more: signs of a vibrant Christian imagination. He did more than represent the land where Jesus walked. Tissot saw himself as a spiritual pilgrim. He reflected on each image and seems to have placed himself in the scenes as the various characters, much as St. Ignatius Loyola recommends in the Spiritual Exercises: as a prodigal son, a child of Jerusalem, a Roman soldier, a mother with a sick child, a condemned thief, a woman at the empty tomb and a convinced follower. Tissot’s visionary images can also help viewers to do the same.”

Writer’s Notebook

One of my greatest joys is to encourage writers as they hone their craft, develop their voice, and live a meaningful writing life. Here are some tips, insights, prompts, and more to help you as you write.

Many of you know that I’m an essay writer. In fact, you might even say I wrote the book on essays! (Just kidding, though I did write a book on essay writing. You can find it here.) One of the my favorite parts of essay writing is writing personal essays, which simply means “Writing as a person,” as author Bill Roorbach describes it. (Note, if you haven’t read his book Writing Life Stories, I highly recommend it for creative nonfiction writers.)

As such, I’ve been thinking a lot about that Scott Russell Sanders quote we talked about above as it relates to essay writing: “Knowing their own vulnerability, they had a livelier sense of what others needed or suffered.” In many ways, this is the heartbeat of the personal essayist. It’s the reason people read first person accounts of someone else’s life and feel heard and understood in their own. Tapping into our own vulnerabilities not only keeps us honest as writers but also helps us better connect with the needs and sufferings of our readers.

Which reminded me of a 2019 Writers Digest article, “Personal Essays: What Should I Write?” where author and writing instructor Susan Shapiro explains a standard writing assignment she gives all her students. Rather than allowing them to “pick a subject that’s lackluster, self-congratulatory, or just a diary-like rendering of something mundane they went through,” (“Sorry, but no editors I know want to publish a piece about how cute your cats, gardenias, or grandchildren are,” she writes) she asks students to write a ‘humiliation essay,’ revealing their most embarrassing secret.

I’m not sure our most embarrassing secrets always make the best essays, but they can serve as a helpful writing prompt to help us write past our insecurities and hesitations into an honest, vulnerable essay. And in the process, we might also learn more about ourselves and others.

So as we enter this Lenten season, take some time to write through the things you’re repenting of. What is God teaching you through the sin he’s asking you to turn from? What truth can you carry back to those who are still struggling with a similar burden?

That’s it for this time! As always, you can hit reply and end up in my inbox. Or you can also leave a comment on this newsletter which will live in the archive over on Substack. It’s one of my favorite features of this platform.

Thanks again for being a subscriber. One of the reasons I write is because of readers like you!

Until next time,

Charity