The Wonder Report: April 29, 2022

A Higher Calling

Happy Friday!

The grass in our front yard has turned so green it’s glowing, the maple saplings the landscapers planted have sprouted tiny leaves, and just when we thought we couldn’t handle one more cold and rainy day, the sun shone so brightly on Saturday and the temperatures rose so high we tried out the central air in our new house. It worked great, by the way.

Of course this week the mornings have been cold again and the afternoons cool. Jacob said it feels like winter all over again after last weekend. But overall, we’ve finally arrived in the spring of our dreams, and we’re spending all the time we can outside.

That time comes with limits, though, since we also have our work to do. Work that includes the tasks of our jobs, but also the tasks of keeping house and parenting and doing good for others. We spend a lot of our time doing the work of living … which is exactly what I want to talk about today. How our work can make us more or less human, depending on how we come to it.

Let’s dive right in.

1. Vocation, Avocation, and the Disappearing “I”

About the time I realized how significant Mom’s needs were following her stroke and how necessary my role as caregiver would become, I heard a sermon about Jesus’ words from the cross to his friend John: “Behold your mother.”

Struggling for each breath, Jesus said so very little from the cross. He prayed for forgiveness for the ignorant crowds. He offered paradise to the repentant thief hanging next to him. He confessed feelings of betrayal by the Father. He complained of thirst.

But he also ensured his mother would be looked after into her old age. He was, after all, her oldest son.

Tears streamed down my face as I heard about God’s heart for adult children caring for their parents. It felt like a calling to caregiving, a vocation I’d never aspired to and unlike anything I’d ever done. It wouldn’t be my “job,” per se. There would be no salary and no benefits. But it was good work I was being commissioned to, and this service, by a preacher I’d never met in a church I was only visiting, was my ordination.

Over the years I cared for Mom, I often found myself overwhelmed and in over my head. Her profound needs often overshadowed my feeble efforts, and we both wore sadness like a veil as her body continuously declined. But no matter how hard it was to provide the care Mom needed, I never once questioned that this was what God wanted me to do.

That’s the benefit of a calling.

::

I’ve felt called to other things in my life, too—ministry positions, jobs, my career as a writer. In fact, most of the time when we use the word vocation, we’re referring to the work—usually paid work—we do.

But God can call us to all kinds of things in life. When my husband and I were dating and considering marriage, I spent some time discerning whether I was called to be a wife and a step-mom. Some people follow a vocation to live in a foreign country. Others take up a social justice issue. A few are called to strict religious orders.

Our vocations—the work we’re given to do—is part of what makes us human. Before sin entered the world, God called Adam and Eve to tend and steward His created world. And the way I read it, work is also part of our eternal calling, just without all the toil and heartache that happened after sin’s arrival.

But now—in this space between—where work is hard and vocations are even harder to discern, how do we know what God wants us to do?

::

For the past several months, we’ve been making a distinction between the spirit of the age—living for ourselves—and the reality of being made by God—that we belong to Him. Using Alan Noble’s You Are Not Your Own: Belonging to God in an Inhuman World* as our guide, we’ve tried to elevate the essence of humanity, rediscovering the good life God intended when he created us.

Because the way things stand, being human has only gotten harder and harder.

According to Noble, for the last several hundred years, being human has increasingly meant having a natural sovereignty, where “to be your own and belong to yourself,” to be “responsible for yourself and everything it entails,” is “the most fundamental truth about existence.”

“No one else has the right to define me, to choose my journey in life, or to assure me that I am okay. I belong to myself,” Noble writes.

Nowhere is this philosophy more apparent than in the workplace, where we make and remake ourselves over and over again by any means possible. In his recent essay, “Resisting a Culture of Incoherence,” Brandon Vaidyanathan, associate professor and chair of the Department of Sociology at the Catholic University of America, writes about the “micro-narratives” we use to create our own callings, “internalizing stories about what strategies to pursue to be a worthy or successful inhabitant of a particular domain.”

“Narrative scripts provide us with information about who we are in a particular realm and the sort of person we should want to become—‘a professional,’ ‘a good mother,’ ‘a disciple’—thus allowing us to evaluate progress, success, or failure. They are the sorts of things we tell ourselves (and sometimes others) to morally orient us to how we should act. They often contain scripted imperatives, which include qualitative distinctions of worth between what is noble or vile, worthy or unworthy.”

But as Noble contends, a society that believes each person is responsible for their own narrative scripts will “develop into a hypercompetitive society, one in which we all must fight for survival, validation, meaning, attention, and affirmation.” Which is exactly what Vaidyanathan found when he interviewed “Christian corporate professionals” about the relationship between their faith and work.

While at church, these professionals would say things like,

“Jesus has to be Lord of all aspects of my life.”

“You have to embrace your cross and die to yourself.”

“I have to forgive even the people who have severely wronged me.”

But in the context of the workplace, where they were living out their “vocation,” the script reflected the hypercompetitiveness of “I am my own and belong to myself.”

“You may not agree with it, but you need to do it to get that promotion.”

“The company doesn’t care about you, so why should you care about the company?”

“What matters at the end of the day is to become more employable.”

But what if we told ourself a different story? How might our true vocations—and our ability to discern them—be different if the narratives we tell ourselves are less about belonging to ourselves and more about belonging to God and to others?

What if our work actually helped us become more human not less?

::

Noble’s book is filled with provocative ideas that have caused me to think more about my life and faith than any book has in a while … which is why I’m still writing about it months after I finished reading it. But one of the more jarring points he made has to do with vocation.

When young people are considering what they want to do for the rest of their lives, a lot of us well-meaning adults encourage them to follow their passions, which turns out to be weak, if not ill-advised, career advice. In part, Noble says, because that advice turns “the focus of our decision-making on ourselves” without little or no concern for others.

“We’d prefer to be paid to do whatever work we find fulfilling, regardless of whether or not it is good for our neighbors,” Noble writes. Ouch.

But equally self-focused is the advice to choose a career that will help others, Noble says. Not because helping others isn’t a good thing, but because sometimes, we try to help people in ways that work well for us and not necessarily for them. When is the last time we told a young person to ask, “What do my neighbors need? What does my community need? What problems can I address?”

“Is it really loving your neighbor if you become a doctor so you can help people, but then you have to leave your community to find a place that needs another doctor? Is that better than staying where you are and becoming a teacher at a struggling public school? … When you perceive your life to be a hero’s journey, even when you try to be intentional about helping others, there’s a good chance you’ll end up with a career that lets you feel helpful” but not actually be helpful.

Here’s where Noble lands: while we should certainly consider our skills and abilities, even our interests and passions, “because we belong to Christ, to His church, and to our family and our neighbors, we must also discern what our community needs. Those needs obligate us.”

In his essay “Acts of Attention,” Robert Cording calls this “the real work of our lives: the work we do not to acquire things but to be, to belong.” This is our vocation, and maybe even our avocation, the things we also are called to, but to a lesser extent. When we’re doing this work, even when it’s hard, we are reminded of Eden—and given a foretaste of the new Jerusalem—because “all our energies are concentrated in the activity itself, and the ‘I’ that too often sees itself toiling [Noble’s "I” that is its own and belongs to itself], disappears,” writes Cording.

I wonder … what needs in your family/church/community might God be calling you to meet? What other questions do you think are just as important to ask when it comes to calling?

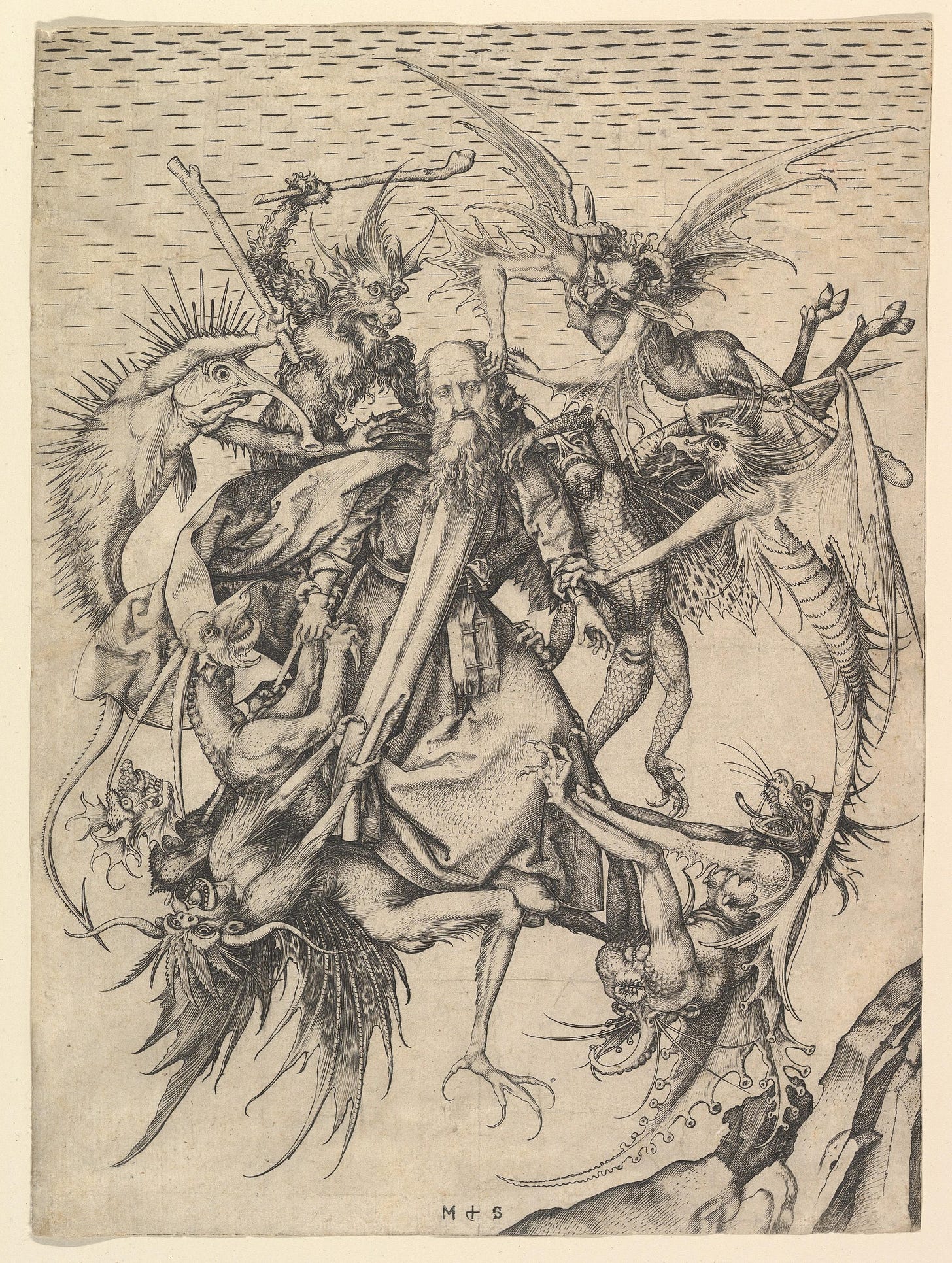

2. “The Unbundled Self of Saint Anthony” (from Schongauer) by Scott Aasman

Comment Magazine recently commissioned a piece of art from Scott Aasman, based on the essay, “Resisting a Culture of Incoherence,” by Brandon Vaidyanathan, which I quoted above. You can see the piece here: “The Unbundled Self of Saint Anthony.”

Aasman’s work was inspired by the Martin Schongauer engraving, “The Temptation of St Anthony,” c. 1470–75.

Here’s Aasman’s statement on his commissioned piece:

“Unlike the traditional St. Anthony, the demons we wage our spiritual battles against are not the grotesque, medieval monsters but the familiar, commonplace false idols we make in the image of ourselves, our communities, and the cultural liturgies we act out. Familiarity disarms us and makes us more malleable and posable, making these cultural mechanisms that tie up the self so effective. We see these temptations enacted in the wilderness of the everyday, and it’s here, like St. Anthony, we make our stand.”

I wonder … What are the similarities between the two pieces? What are teh differences? Which one do you find yourself most drawn to? Which do you identify with the most? Why?

3. “How to Cultivate Joy Even When It Feels in Short Supply” by Tish Harrison Warren

I’m going slightly off-topic by sharing this essay, but it feels just right for the season.

In the liturgical calendar, Easter is not just one day to celebrate—as I was taught most of my life—but a whole season, like Christmas. Eastertide lasts 50 days, and as Warren explains here, it’s a season that says, “Now, celebrate. Now, begin to notice what there is to be joyful about. Now, pay attention to goodness.”

And it does it without irony ... because we’ve just spent 40 days before that in a season of penitence. See, the joy of Easter isn’t a denial that the world is still cursed with sin or a refusal to admit there’s plenty in our lives NOT worth celebrating. Rather, it’s an acknowledgment that both joy and despair exist closely together in this life. And for the next, joy has already won.

“For Christians, joy has deep roots. It springs from the hope that Jesus is risen and is making all things new. Easter is a season of joy not because we insist that the glass is half-full but because Jesus himself, the Bible says in Ephesians, ‘fills everything in every way.’ This means that death is real, but there’s something greater than death. Injustice is real, but it’s not the end of the story. Heartbreak is real but it gives way to redemption. Suffering is real, but it cannot erase beauty.”

This essay was originally published in Warren’s subscriber only newsletter for The New York Times, but since I’m a subscriber, the Times makes it possible for to share the essay with you for free here.

Well, that’s it for this issue. Thanks again for joining me here for another week. It’s a privilege to share this space with you and to enter into these conversations together.

As always, if you’d like to send me a note or ask a question, you can hit reply and end up in my inbox. Or you can also leave a comment on this newsletter, which will live in the archive over on Substack.

By the way, if you’re planning to join me for the Kate DiCamillo summer reading, you can find the schedule for all 25 books here. If you’d like to participate in a less-involved way, here’s the schedule: The Tiger Rising (June), The Tale of Despereaux (July), and Flora and Ulysses (August). I’ll be sharing the complete details for the summer two weeks from today.

Until next time,

Charity

Thank you so much for writing about your experience as a caregiver. It really touched me. I was just contemplating getting a part-time job this summer after school is out, but as my parents' health is declining, I think God is calling me to help them out as much as I can, it is getting to be multiple doctor appointments each week and it seems like a new medical issue or a medical issue that isn't getting better. I appreciate you sharing your full experience. Sending you love and joy.