The Wonder Report: April 22, 2022

The Good of Our Neighbors

Happy Friday!

On Sunday morning, our church, along with Catholic and Protestant Christians around the world, celebrated the resurrection of Jesus. (Our Orthodox brothers and sisters will celebrate this Sunday.) One Easter tradition that our small congregation observes has become especially meaningful to me over the past couple of years: flowering the cross.

Members of the church bring flowers from their yards or bouquets they’ve picked up from the grocery store, and then the flowers are attached to the cross on Easter morning. This custom dates back to the 6th century and is a visual reminder of God’s power to transform a brutal Roman torture device into an act of love and new life.

How was your Easter? What’s a tradition you’re especially fond of? I’d love to hear how you celebrated.

After a three-week break to talk about art and the Easter season, we’re back to our theme of being human and what it means to belong to God. We’ll spend three more weeks on the topic before we transition to something fun for summer.

Let’s get started!

1. Who’s My Neighbor?

Netflix recently began streaming a new series called Old Enough! It’s a Japanese reality show where very young children (ages 2-4) are sent out to run errands on their own. Of course they aren’t really alone, at least not for the show. A camera crew follows along, and the children are mic’d up so you can hear them talking to themselves. A narrator comments on their every move. But the show represents the Japanese value of “raising smart, capable kids whose parents enable them to practice autonomy without sacrificing safety,” according to NPR’s Michaeleen Doucleff.

Before I go any further, I’ll admit that I haven’t seen the show. We recently gave up our Netflix subscription and, so far, aren’t looking back. But I was particularly intrigued by the article written in response to the show by Doucleff, who asked her own 4-year-old daughter to run an errand to the grocery store two blocks away from their urban apartment.

There’s so much to say about giving such young children this level of autonomy. Responses to the show Old Enough! have run the gamut, as you can image. In fact, an editor’s note at the top of Doucleff’s article even informs readers that in some places, “parents who allow young children to run errands or go places without adult supervision may violate local laws.”

But the thing I really want to talk about is one key point in the “how-to” section of Doucleff’s piece, an idea that’s also at the heart of the Old Enough! show and is fundamental among the indigenous cultures Doucleff researched while writing her own parenting book. She describes how she prepared her daughter for months before sending her out on her own. She taught her how to navigate intersections, stop at crosswalks, look for cars, and proceed slowly when it’s safe. She trained her how to walk the family dog so she’d never really be alone. She started with shorter errands, like taking out the garbage, and worked up to the grocery store.

But then she said this:

“During this training time, I also made sure she knew our neighborhood well. I introduced her to neighbors that we knew as well as the clerks who work behind the counter at the market. So she had allies around every corner – and extra eyes keeping her safe.”

That is the part that made the whole concept of preschooler autonomy so uncomfortable for me. Inherent in parenting that is “built on cooperation instead of control, trust instead of fear, and personalized needs instead of standardized development milestones”—inherent an all kinds relationships that provide a safety net for the most vulnerable among us—is something so simple but all-too rare in 21st century life: We have to know and trust our neighbors.

::

Jim, Carol, Grace Ann, Debi, Pam, Diane, Joe, Michelle, Arnie. These are some of our neighbors in our new neighborhood. They’re the ones we’ve met so far, the ones whose names we remember. There are other neighbors we wave to and a few who stop to pet our dogs. We’ve talked to the guy two houses down but haven’t asked his name yet. We see the neighbors on the corner through their open blinds at night. Other neighbors are just starting to emerge now that the weather’s warming up.

But even getting this far has taken a lot of work. It’s required me to stand and chat in the driveway when I had other things to do. It’s meant stopping in the middle of walking the dogs—dogs who really don’t like to stop—to chat up strangers. Sometimes, I don’t wave or stop or take the time to talk. But every time I do, I feel a little more human.

In an op-ed for Utah’s Deseret News, Daniel Cox, the director and founder of the Survey Center on American Life, writes about how little people know their neighbors now.

“The United States is a nation with an incredible amount of racial, political, religious and geographical diversity. It’s no wonder that we don’t often agree with each other,” Cox writes. “But diversity is not the source of our current problems. Instead, it’s that we have become deeply incurious about each other, no longer interested in getting to know even the people who live next door. We live in a nation of strangers. Even when we do talk to our neighbors we’re increasingly doing it online, using platforms like Nextdoor or Facebook.”

There are a lot of reasons people don’t know their neighbors. For one, we’re all so busy. Many people spend hours in the car driving back and forth to work (though the pandemic may have curbed some of that). Parents rush from work to after-school activities, often spending hours in the evenings and weekends at ball fields or in concert halls or waiting outside dance studios. In the suburbs, most of life is spent in vehicles, rather than walking or taking public transportation, with trips beginning and ending inside garages. And then there’s the Internet, which allows us to run errands from the sofa and communicate with people from around the world, with whom we share far more in common than the people who just happen to live next door to us.

But what about the idea of being incurious, of actually not even wanting to know our neighbors even if we did have the time? What if this lack of curiosity is actually making us less human? What if the things that are taking us away from our neighbors—all our efforts to pursue our own good—are actually keeping us from pursuing the good of those around us? And what if even “those neighbors”—the ones that are awkward or nosy, the ones that tell off-color jokes or don’t pick up after their dogs—are somehow given to us by God to love?

In his book You Are Not Your Own: Belonging to God in an Inhuman World*, Alan Noble writes about all the ways that belonging to God means we belong to others. Some of these connections seem obvious: If we belong to Christ then we belong to his church. And if we belong to Christ then we belong to our families. But our connections run broader than that.

“We are united to Christ and His body through the Lord’s Supper and baptism. We are united to our families through blood and shared history. We are united to our neighbors through our shared humanity, our sin nature, our need for redemption, and our shared civic experience,” Noble writes. “Your belonging to your neighbor is a subsidiary kind of belonging: because you belong to Christ and He has commanded you to ‘do good to everyone’ (Gal. 6:10), you have a deep obligation to care for the interests of your neighbor.”

::

Jesus said it most clearly when he told the crowd to “love your neighbor as yourself.” A religious leader, “wanting to justify himself,” raised the question: “Who’s my neighbor?” And Jesus humored him by telling the parable of the Good Samaritan. In the story, He explores the outer limits of neighborliness. But when he gets to the end, Jesus turns the question back on the asker, pointing to three different characters who each responded differently to the man in need. Who “proved to be a neighbor”? Jesus asked.

That’s really the extent of it: our neighbor is whomever we encounter, despite how different they may be. Most of us know this, though we dismiss the obvious people who live next door to us by playing our own kind of verbal gymnastics with the definition of neighbor. The people in our online Facebook group, the people we work with at the office, the other parents of our son’s teammates, the people we play Words with Friends with: yes, they are all our neighbors. So are the displaced people of Ukraine, the starving children in Ethiopia, the latest victims of natural disasters. Even the people who watch Fox News or CNN, the Twitter users we wrangle with, and voters from the other party who cancel out our votes. They’re all our neighbors.

But so are your actual neighbors, the ones who live next door to you, drive down the same street, and have the same mail carrier. We’re so used to exploring the far boundary of who our neighbor is that we sometimes overlook the ones closest to us. And in case you’re concerned about caring too much for these nearby neighbors and not the others, don’t worry.

“You cannot desire the good of your non-Christian neighbor too much. It is not possible,” Noble writes.

“However much you desire for your non-Christian neighbors to receive justice and know God’s love and mercy and to be treated rightly as human persons made in God’s image, you could always desire their good more. In contemporary America, our temptation is to care too little, not too much. Our tendency is to think of ourselves as totally independent of our street, neighborhood, and city. But we have an obligation to them. That obligation is subsidiary in the sense that it is a derivative belonging, rooted in and bound by our all-encompassing belonging to Christ.”

::

I’m not sure I’d ever know my neighbors well enough to send a 4-year-old to the grocery store on her own. (I still worry about our 18-year-old driving after dark.) But I am interested in living where there are allies around every corner – and extra eyes keeping us all safe. There’s real joy in this kind of belonging, where progress isn’t measured by dollars or minutes but by how welcome people are made to feel. "It is a lifelong project and we will make mistakes,” Noble writes, but it makes us all more human, in the best sense of the word.

I wonder … how well do you know your neighbors? How curious are you about them? How are your neighbors like you? How are they different? How would you describe your neighborhood to someone who just moved in? How could you make them feel welcome?

2. “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid: It’s not just a phase” by Jonathan Haidt

Set aside a good 20-30 minutes to read this article; it’s definitely worth it. What Daniel Cox hinted at in his op-ed (quoted above), Jonathan Haidt explores in depth: the role of social media in keeping us from, and even turning us against, our neighbors. This article explores some political themes, but it does so by looking at the ways social media has fostered extreme views on both sides. In the end, I don’t know anyone who wouldn’t nod their head in agreement at the idea that American life has felt “uniquely stupid” over the past 10 years. This article tries to explain why and what we can do about it … and it starts with getting to know your neighbors.

“The story I have told is bleak, and there is little evidence to suggest that America will return to some semblance of normalcy and stability in the next five or 10 years. Which side is going to become conciliatory? What is the likelihood that Congress will enact major reforms that strengthen democratic institutions or detoxify social media?

“Yet when we look away from our dysfunctional federal government, disconnect from social media, and talk with our neighbors directly, things seem more hopeful. Most Americans in the More in Common report are members of the ‘exhausted majority,’ which is tired of the fighting and is willing to listen to the other side and compromise. Most Americans now see that social media is having a negative impact on the country, and are becoming more aware of its damaging effects on children.”

3. Kate DiCamillo Summer Reading

I know not everyone will want to read along with me this summer as I attempt to read Kate DiCamillo’s entire collection of books (except the picture books. I’ve decided not to include those). But for those who are interested, I wanted to share the reading schedule.

As I mentioned, this is going to be an intense reading experience. There are 25 books, though some of them can be completed in a single setting because they are for younger kids. For those who want to read the whole collection, I’ll be creating a separate Substack post for each book where you can read a short overview and find discussion questions to think about for yourself and/or respond to in the comments section. You’ll be able to subscribe to receive those posts in your inbox, or they will be linked in each week’s Wonder Report. More details will be available for that option in mid-May.

If you don’t want to read all the books but would still like to participate, I’ve chose three of Kate’s stand-alone books to read and write about over the summer for my broader Substack audience. You won’t need to read the books to enjoy the essays, but it would be a way to read along without the larger commitment. Those books are The Tiger Rising (June), The Tale of Despereaux (July), and Flora and Ulysses (August).

In case you’re wondering why I’m attempting to read all of DiCamillo’s books in one summer, you can read more here:

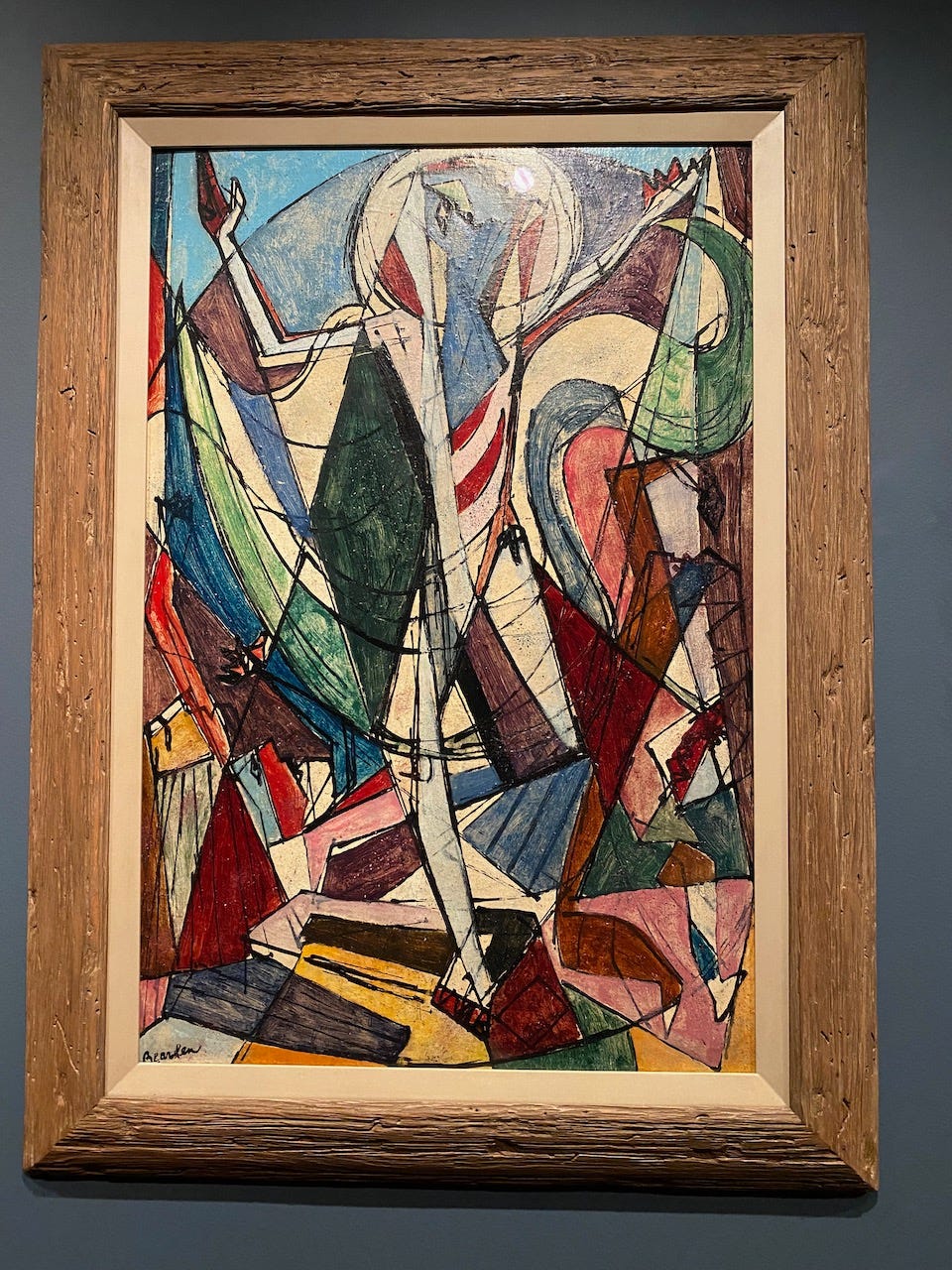

4. “He Is Risen” by Romare Howard Bearden

As we continue through the Easter season, I wanted to share this painting by African American artist Romare Howard Bearden, who created this piece as part of his series The Passion of Christ after his service in the U.S. Army during the Second World War.

I saw this painting during a recent visit to the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. According to the gallery notes, “This work, previously owned by the jazz musician Duke Ellington, shows the culmination of the Biblical narrative, as Christ triumphs over death and raises His arms to heaven.”

We’ve come to the end of another Wonder Report. Thanks for joining me here each week. It’s a privilege to share this space with you and to enter into these conversations together. It’s my favorite part of the writing life.

As always, if you’d like to send me a note or ask a question, you can hit reply and end up in my inbox. Or you can also leave a comment on this newsletter, which will live in the archive over on Substack.

Until next time,

Charity

Oh Charity, just today I was going to send you a link to an interview with Jonathan Haidt in which he unpacks this essay with Andrew Sullivan (The Dishcast) because of the social media question! I hadn't read the essay—now I can! Also, so interesting what you explore here about parenting, autonomy, freedom et al (views differ hugely here in the UK, too. I'm betting you can guess where I land! :) Like you!). Also, I know it's old, but have you seen the Susan Pinker TED TALK, The Secret to Living Longer/Italian Blue Zone? She talks about exactly this when it comes to knowing our neighbours and living truly in community. Loved all of this.

Hi Charity. I could comment on your newsletters almost every single week, but don't always have the time. I am currently visiting our son in seminary this weekend. As I thought about neighbors, I thought about last night. We drove the 8 hours here and then took him to an early dinner. Then he said we could wait at his apartment while he helped his friends move. We went along. The seminary has a sort of gated community and has married housing, married with kids housing, etc. So we pitched in and moved her from one third floor to another. She had a pile of goods that were going to the sharing house. Our seminary has something similar. Students can go and pick up furniture or other things that people didn't need. In fact, the couch in my son's apartment came from another student who didn't need it. Also, they go in and out of each other's apartments.

The friends were gathering after the move to eat pizza and just visit. I have so much to learn from that. His apartment was not perfect. In fact, this was the son who used to tease me about cleaning our house up perfectly before guests came. "Mom, the president isn't coming!" And yeah, he doesn't care that stuff is strewn everywhere. His friends didn't care either.

Finally, I wanted to comment on losing curiosity. I participate in the American Exchange Project. I am just going to link my blog post about it rather than summarizing. We enjoyed hosting the young people and will be hosting some new ones again in June. I love this project.

https://travelingwiththefather.christinelangford.com/traveling-to-understand/

Thanks again for all of the work you put into this newsletter.

Christine